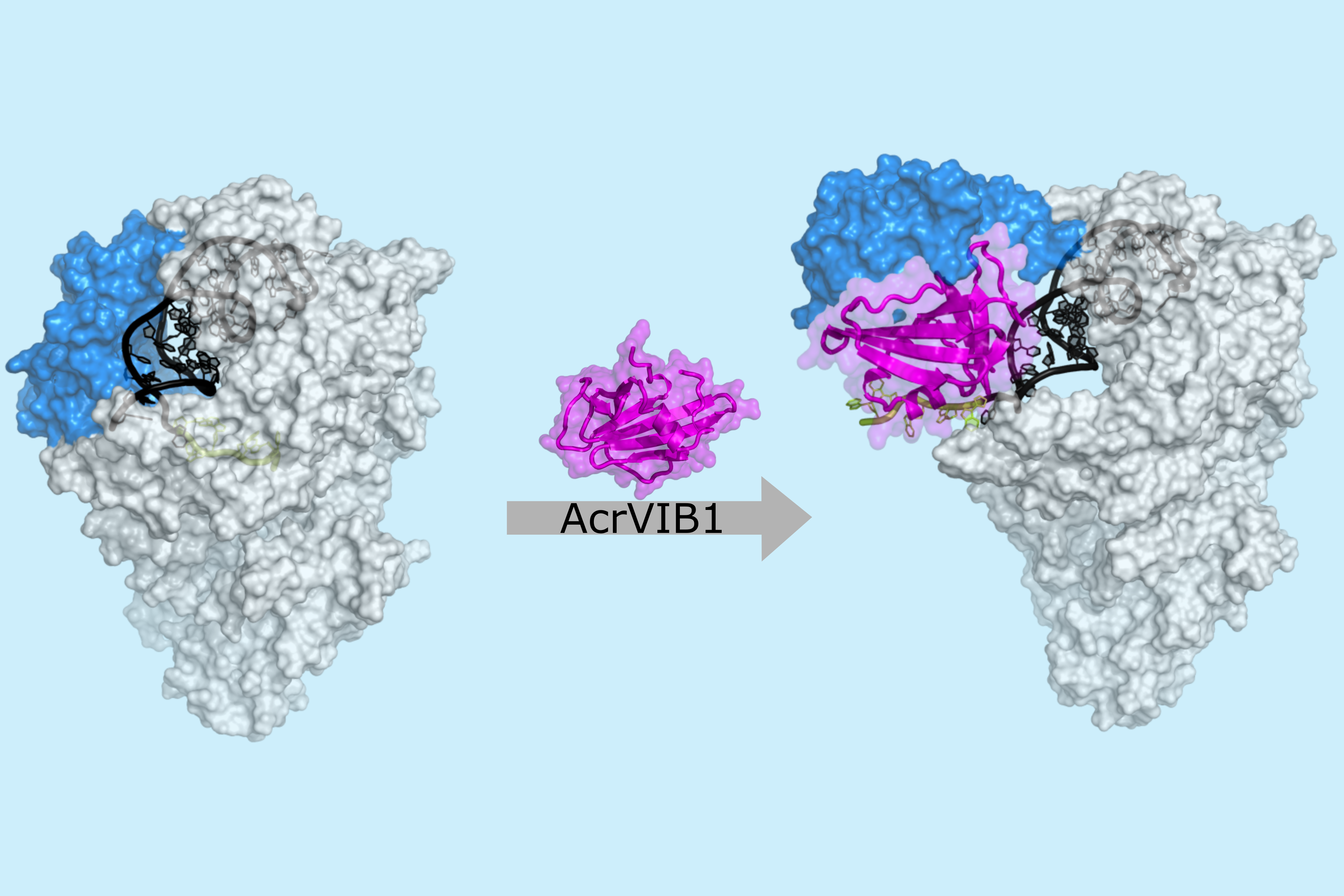

CRISPR-Cas systems, also known as gene scissors, only work if there is a specific DNA sequence, known as the PAM sequence, next to the desired cutting site. This marker serves as a reference point for the Cas enzymes, without which they cannot find the genome site to be cut. As a result, not every part can be edited with the same ease, and many disease-causing mutations cannot be targeted.

A solution to this problem may lie in the past of the gene scissors: Over the course of evolution, Cas enzymes have been optimized for specific bacterial needs, but this has also limited their function. Their ancient ancestors may have been more versatile and thus able to recognize more DNA targets.

Chase Beisel wants to harness these forgotten functions for biotechnology: "Think of it as combining archaeological excavation and technology development. We're excavating the genetic past to build the medical future." The affiliated department head at the HIRI, a site of the Braunschweig Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) in cooperation with the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU), is receiving a Synergy Grant of ten million euros from the European Research Council (ERC) for this purpose. Beisel’s subsequent move to the Botnar Institute of Immune Engineering (BIIE) in Basel, Switzerland, in 2025 positions the project within an institute dedicated to translating immune engineering research into solutions for global child and adolescent health—a mission that aligns with RGNcestry's goals. Besides Beisel, the project team includes Samuel Sternberg (Columbia University, USA), Raúl Pérez-Jiménez (CIC bioGUNE, Spain), and Israel S. Fernández (Biofisika Institute, Spain).

Beisel and Pérez-Jiménez had already reconstructed CRISPR proteins that are two to three billion years old. In doing so, they discovered that these proteins have remarkable properties, which differ from those of their modern counterparts. These include the ability to recognize a broad spectrum of DNA targets or to cleave other nucleic acids upon activation.

Such functions not only raise questions about the early evolution of life, but also open up new possibilities for tailor-made biotechnological applications. In the long term, these technologies could enable therapies for genetic diseases that cannot yet be treated with today's CRISPR technology. Robust diagnostic tools that can be used worldwide and in resource-poor regions are also conceivable.

From HIRI to BIIE

The ERC Synergy Grant was awarded to HIRI, where Chase Beisel developed the application as department head. Following Beisel's appointment as a faculty member at the Botnar Institute of Immune Engineering (BIIE), the grant will transition to BIIE, where it will be conducted over the next six years and will leverage BIIE's expertise in translational research and its state-of-the-art facilities for developing the next generation of gene-editing and diagnostic tools. The institutional transfer is being coordinated with the ERC, with BIIE serving as the host institution leading this international collaboration.