Bacteria contain a wide variety of mechanisms to fend off invaders like viruses. One of these strategies involves cleaving transfer ribonucleic acids (tRNA), which are present in all cells and play a fundamental role in the translation of messenger RNA (mRNA) into essential proteins. Their inactivation limits protein production, causing the infected cell to go dormant. As a result, the attacker cannot continue to replicate and spread within the bacterial population.

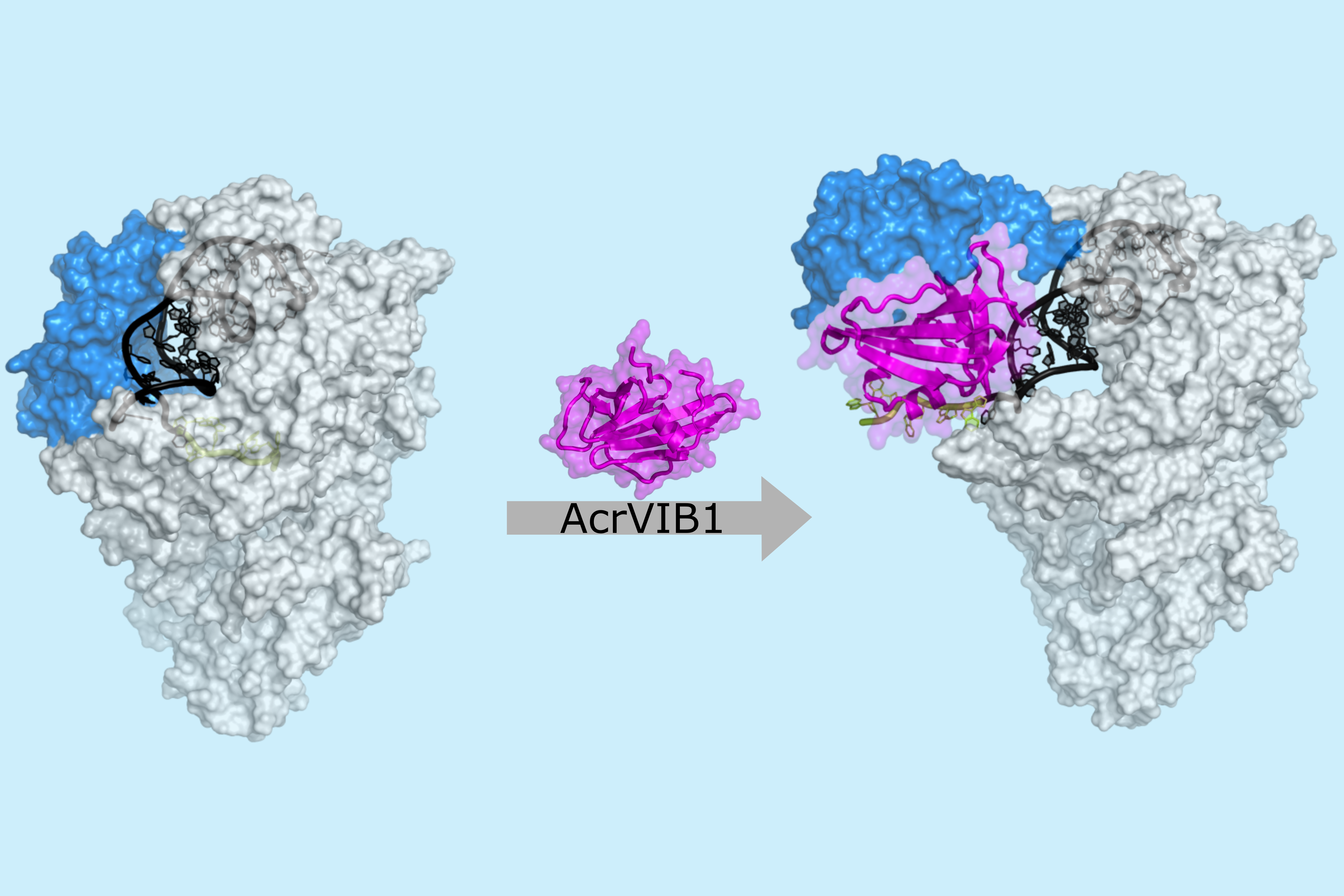

One common bacterial defense that has so far not been associated with tRNA cleavage are CRISPR-Cas systems. CRISPR uses RNA-guided proteins, known as Cas nucleases (from CRISPR-associated), to recognize invaders based on their genetic material and deactivate them. Once they identify a pathogen, the nucleases trigger an immune response unique to each system. This includes, for example, cleaving foreign DNA or halting growth through widespread RNA and DNA degradation. These mechanisms have already been employed by mankind in many ways, and CRISPR has been recognized as an important foundation for genome-editing technologies. However, it was not known until now that CRISPR-Cas also preferentially targets tRNAs as part of an immune response.

An unexpected discovery

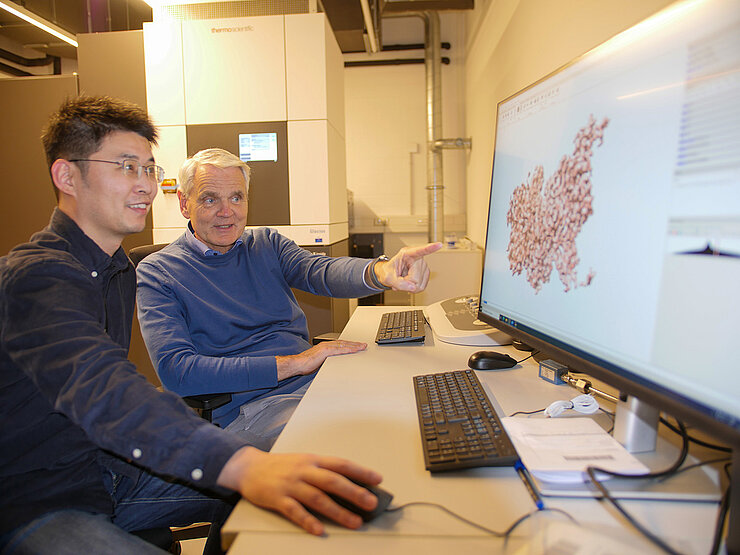

Researchers at the Helmholtz Institute for RNA-based Infection Research (HIRI), a site of the Braunschweig Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) in cooperation with the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU), have collaborated with scientists from the HZI and Utah State University (USU) to discover a novel CRISPR mechanism that targets tRNAs. “These findings were completely unexpected,” says Chase Beisel, affiliated department head at the HIRI and corresponding author of the study, which was published today in the journal Nature. “Our team was actually working on proteins associated with a unique nuclease called Cas12a2”, adds Beisel.

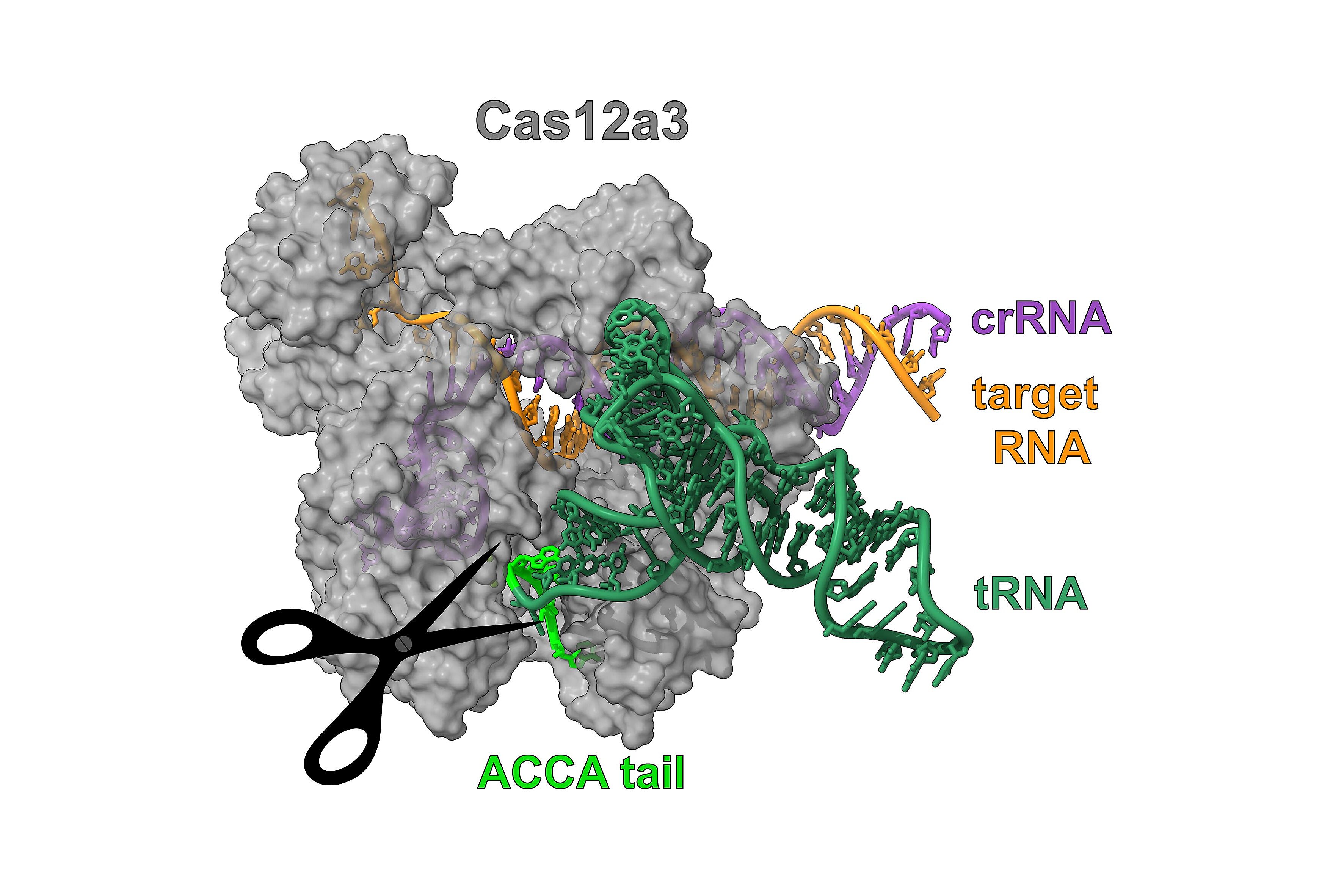

In two studies published in the journal Nature in January 2023, teams that included Chase Beisel described how they had found Cas12a2 in a family of nucleases that exclusively cleave DNA. In contrast, Cas12a2 was able to broadly cleave both RNA and DNA. “We hypothesized that this protein family might contain other special functions. And we were right: we found Cas12a3 with its unique properties,” adds Oleg Dmytrenko, former postdoc in the Beisel lab and first author of the study recently published in Nature.