Antibiotic-resistant infections are a growing threat worldwide. Instead of culturing bacteria in the traditional way and testing their response to antibiotics, laboratories are increasingly analyzing bacterial genetic material to spot resistance early. From DNA sequences of a pathogen, researchers can deduce its resistance mechanisms and identify effective treatment options. Computer programs that "learn" from existing sequencing data are a promising way to predict which antibiotics will work and which will not. However, these technologies also have shortcomings: One often underestimated challenge is the assumptions made by the computer-based methods themselves.

Researchers from the Helmholtz Institute for RNA-based Infection Research (HIRI) in Würzburg, a site of the Braunschweig Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) in cooperation with the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU), together with the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, have been able to demonstrate that these very assumptions can lead to overly optimistic results regarding how well the prediction works, and can thus distort its significance.

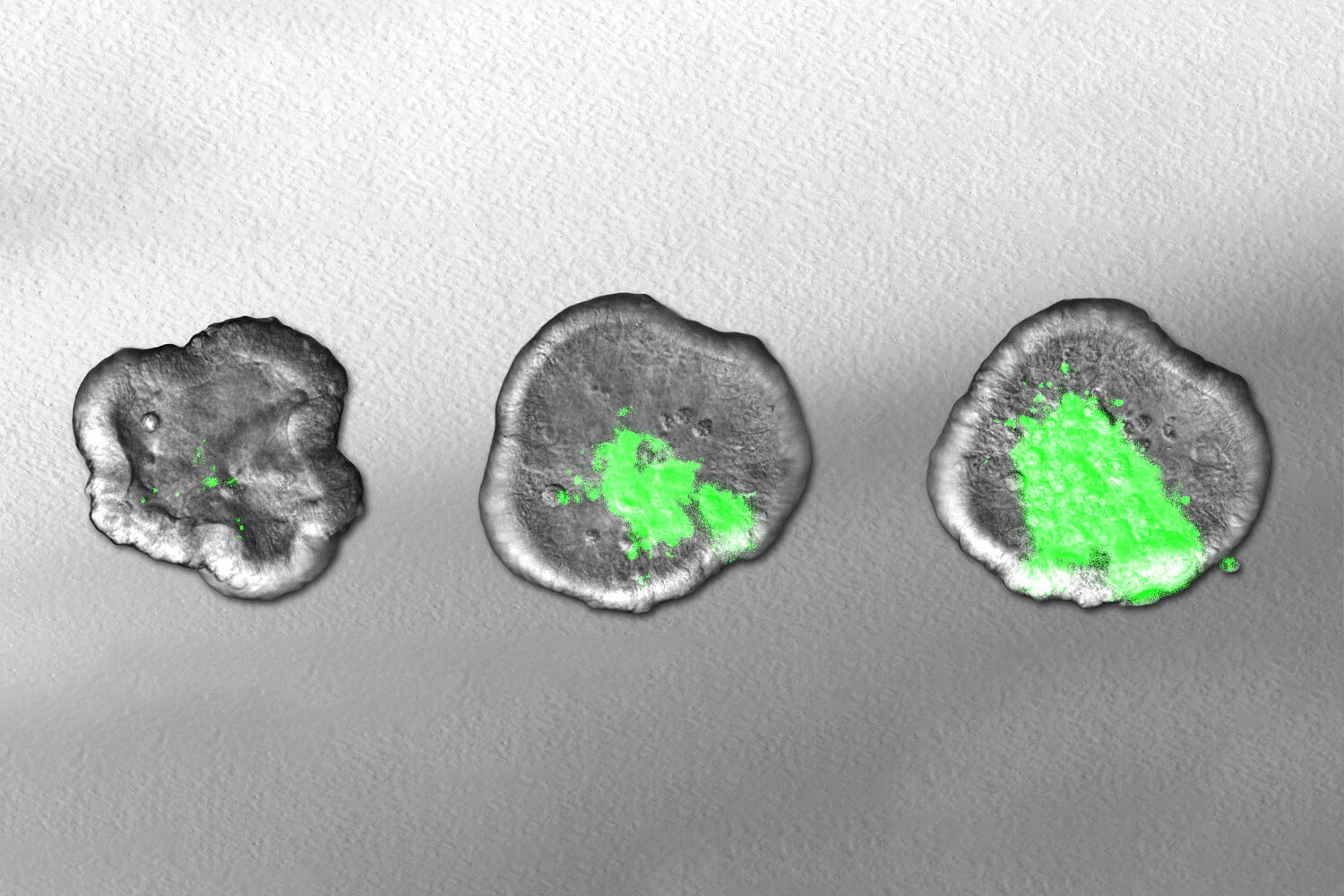

Most classic machine learning methods—technologies that learn from data and recognize patterns independently without explicit programming—require training data to be independently and identically distributed. However, this is not the case with bacterial samples: Closely related bacteria share many common characteristics. During an epidemic, "successful" variants quickly prevail. If they multiply rapidly because they have defense mechanisms against antibiotics, among other things, then other characteristics are automatically spread as well – even if they are not related to resistance.

This can create the false impression that certain genetic characteristics are directly linked to resistance when, in reality, they only co-occur because the pathogens are related. The algorithms therefore learn to predict related strains rather than resistance itself.

24,000 genomes from five bacterial species

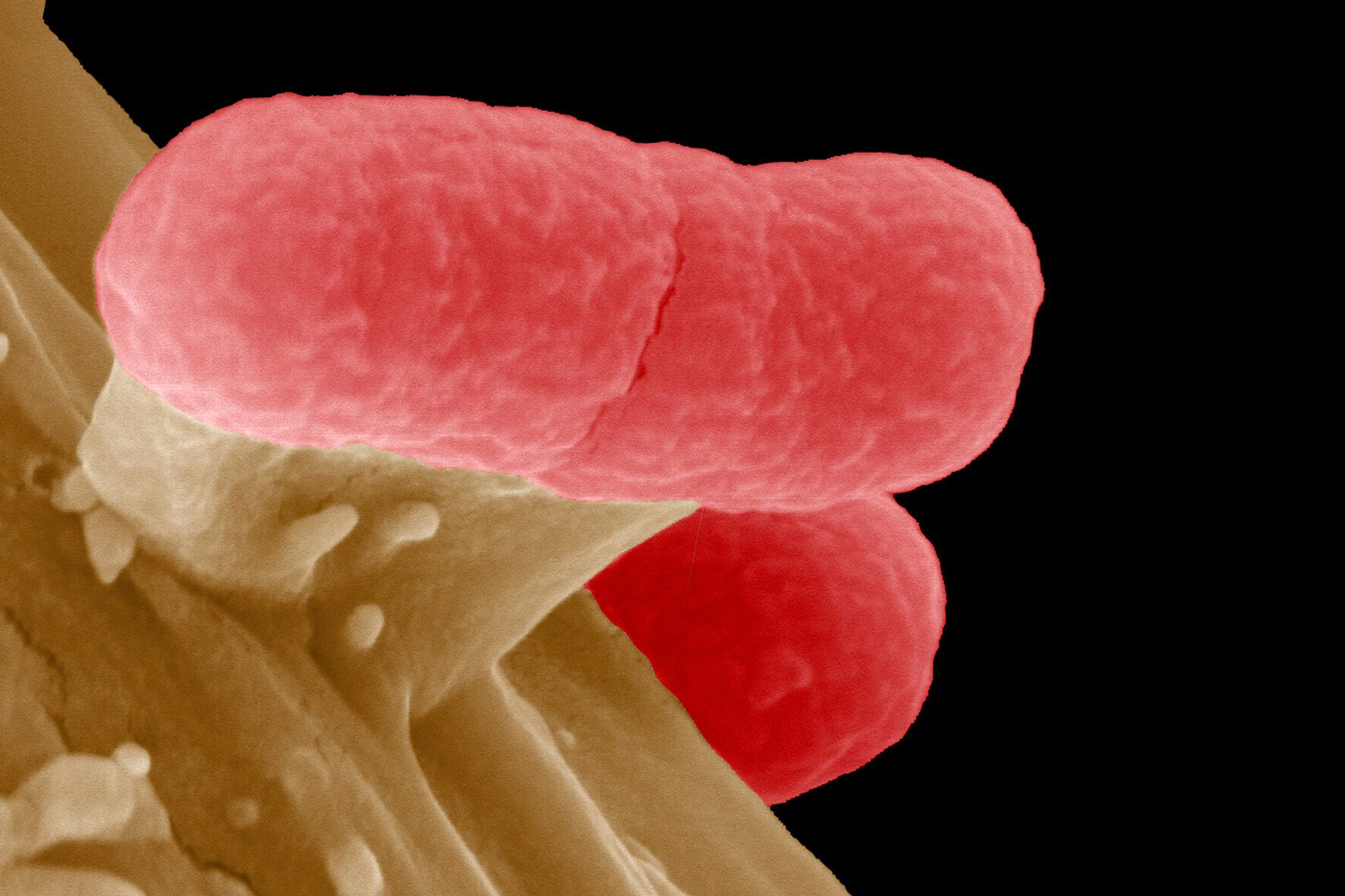

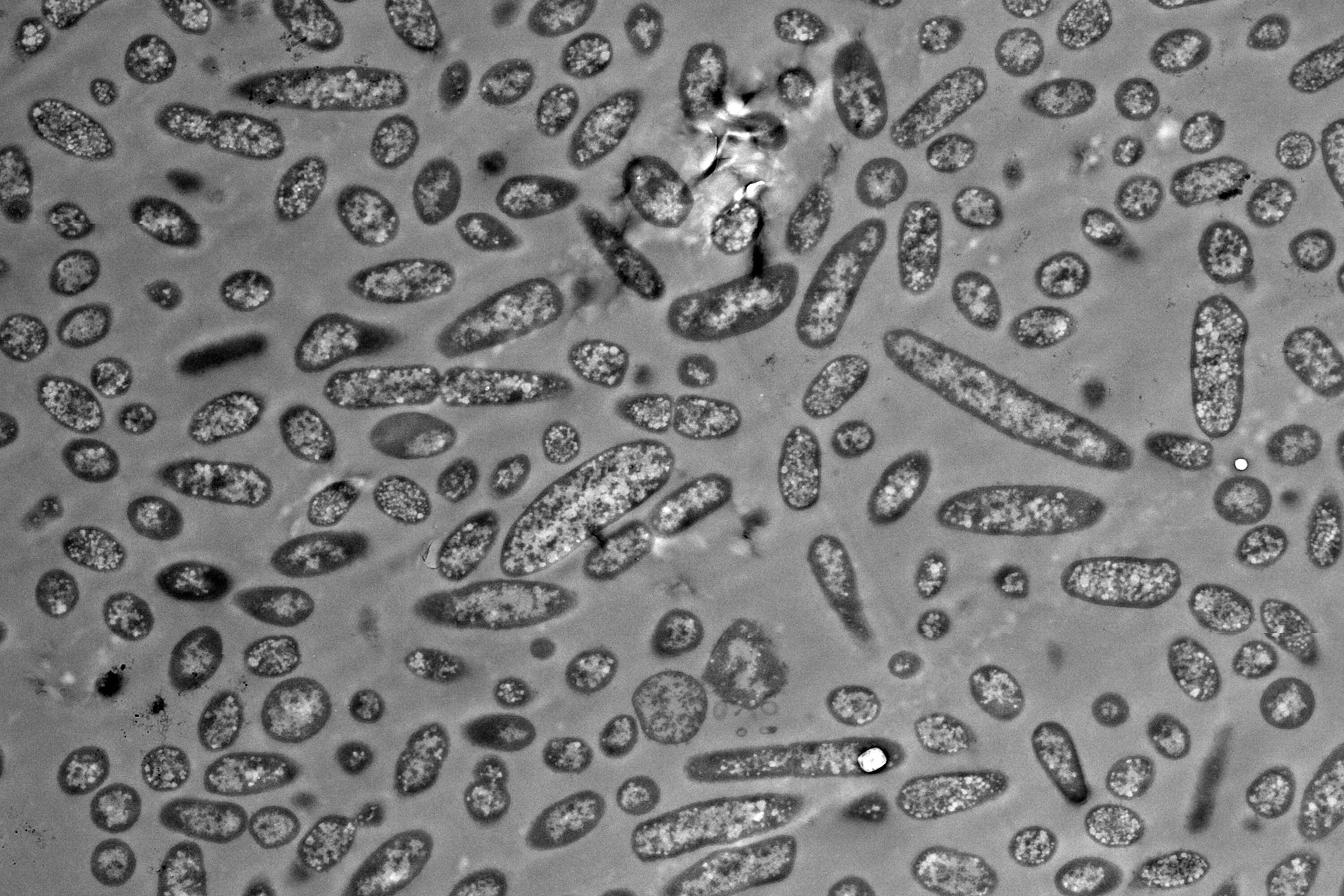

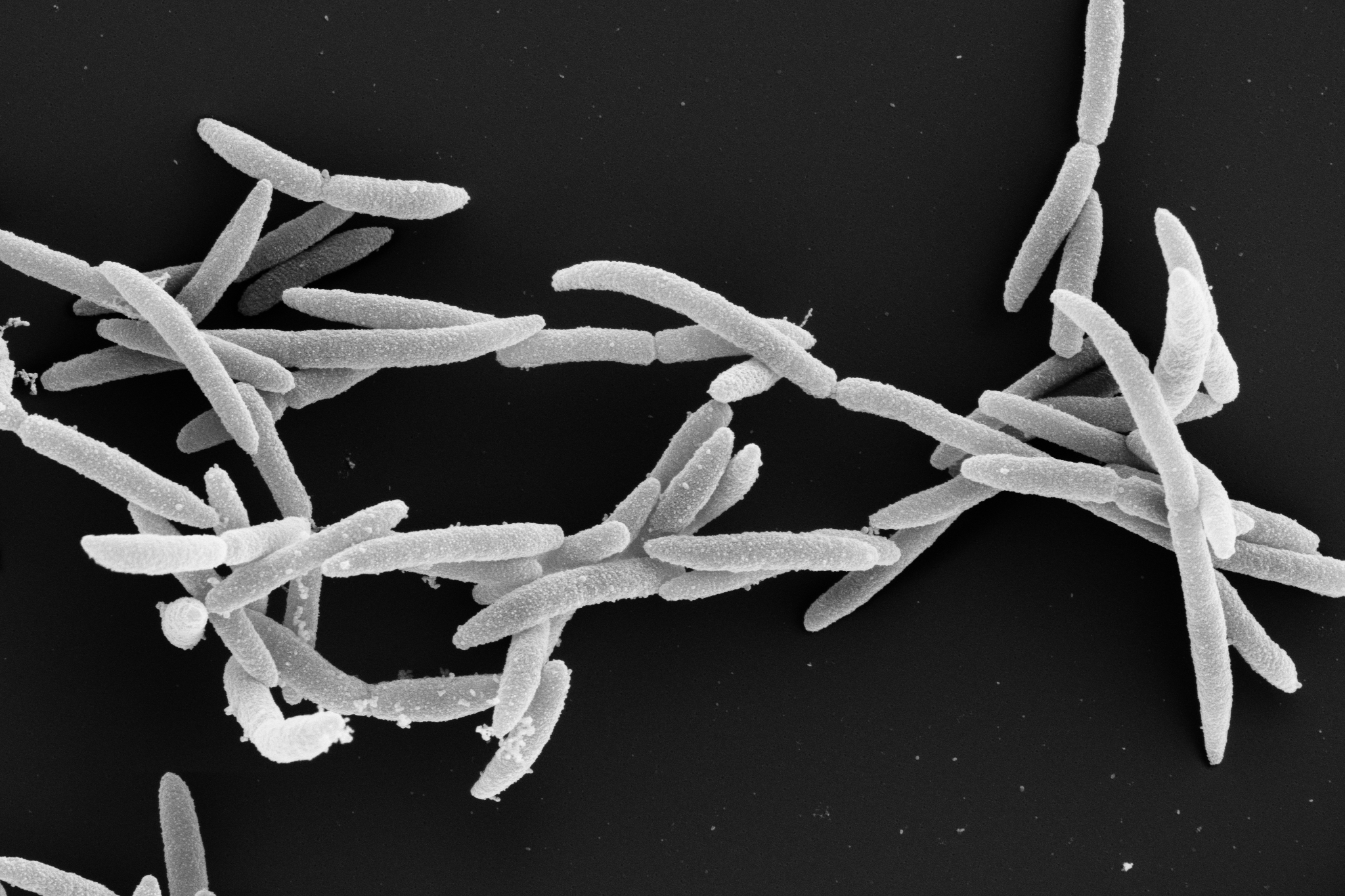

"In this project, we analyzed more than 24,000 genomes, the entirety of all genetic information, from five major disease-causing bacterial species," says Lars Barquist, a scientist associated with HIRI and professor at the University of Toronto in Canada. Barquist initiated the study, which was published in PLOS Biology, as the corresponding author. The bacteria in question are the gastrointestinal and urinary tract pathogen Escherichia coli, the opportunistic pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae, the gastrointestinal pathogen Salmonella enterica, the skin commensal and opportunistic pathogen Staphylococcus aureus, and the main cause of community-acquired pneumonia, Streptococcus pneumoniae. For these germs, common machine learning methods provide an overly positive picture of how well resistance prediction works.

"We wanted to investigate how biased sampling affects the performance of machine learning tools for predicting resistance," says Barquist. The researchers constructed scenarios where resistance is entangled with bacterial family trees. Thus, they were able to show that conventional approaches can lead to overly optimistic results that cannot be generalized. "When the models are evaluated more realistically by ensuring that the training and test bacteria do not come from the same genetic family, the accuracy drops—sometimes sharply," notes first author Yanying Yu, who pursued her PhD in Lars Barquist's lab. These results suggest that models which do not account for evolutionary relationships among bacteria may fail to capture true resistance signals, thereby limiting their ability to make accurate predictions in previously unseen strains. As a consequence, such methods are unlikely to provide reliable guidance for precision treatment as new pathogenic lineages emerge.

The study provides a comprehensive overview of the extent of this problem: "Many previous method evaluations were probably too optimistic," concludes Barquist. "In order to develop reliable tools for predicting antibiotic resistance, it is essential to consider the evolutionary relationships of bacteria," notes Yu.

The research results provide valuable starting points for the development of improved testing methods and data sets and can serve as a guide for future models and monitoring systems. In this way, they promote new methodological approaches that take into account the structure of bacterial populations and thus enable more accurate predictions.